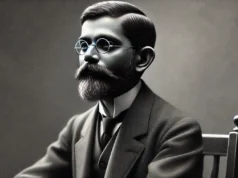

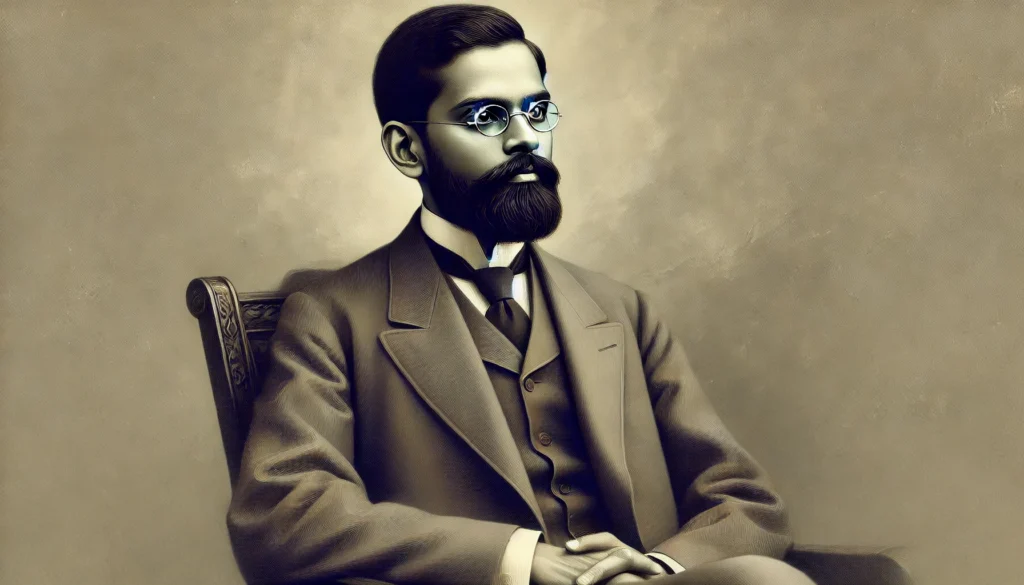

S.K. Rudra was born in Bengal on January 7, 1861. He taught at St. Stephens from 1886, Delhi and became its first Indian principal from 1907-1923 – perhaps the first Indian principal of any institution established by missionaries.

Overcoming Barriers

Rudra’s appointment as St. Stephens’s first Indian principal was not easy. Thanks to the paucity of applicants and the vociferous support of C.F Andrews, a missionary and professor at St. Stephens, Rudra was eventually, after much descension, appointed as Principal.

Indianising St. Stephen’s: Rudra’s Reforms and Impact

As its principal, he helped Indianise it, ensured equal pay for European and Indian staff, and contributed to its growth and reputation. Under Rudra’s leadership Intellectuals, politicians, faculty and senior students would regularly meet in the college to discuss issues related to India’s civil rights. These discussions piqued Rudra’s interest in Gandhi’s civil disobedience in South Africa.

Susan Viswanathan, argues that Gandhi’s return to India after 28 years was largely due to Rudra persuading C.F. Andrews and W.W. Pearson to go to South Africa and convince Gandhi to return to India and replicate what he was doing here in India.

Participation in the Non-Cooperation Movement

Although he was part of an institution that was very British, his participation in India’s freedom was very unique. It was in Rudra’s home that Gandhi drafted the Open Letter to the Viceroy and the Non-Cooperation Movement.

His role in the freedom struggle was taking the risk of hosting Gandhi at his official residence as principal of St. Stephens. Gandhi initially hesitated to stay with Rudra fearing that it might cast Rudra, Christianity and the college in bad light, but Rudra insisted.

Gandhi’s fears were not misplaced, the then chief commissioner of Delhi advised the leadership of St. Stephens to dissuade Rudra from entertaining Gandhi at the official residence of the principal. Gandhi quotes Rudra’s reply to him in a tribute that he wrote after Rudra’s death,

“My religion is deeper than people may imagine. Some of my opinions are vital parts of my being. They are formed after deep and prolonged prayer. They are known to my English friends. I cannot possibly be misunderstood by keeping you under my roof as an honoured friend and guest. And if I ever have to make a choice between losing what influence I may have among Englishmen and losing you, I know what I would choose. You cannot leave me.” (2015, p.59)

Faith and Public Life

Rudra’s faith was not separate from his public life. His faith helped him reconcile the different obligations as an Indian, Christian, friend of Gandhi and the Principal of a mission college. His faith did not distance him from temporal concerns of the Indian Freedom struggle, instead it fuelled his engagement with it – helping him harmonise his beliefs and his actions.

Being Christian, Being Indian

Despite Western influences, Rudra remained devoted to his country, its people, and its progress. By no means did his faith come in the way of his identity as an Indian, it only enhanced it. Rudra championed the idea of an independent Indian-Christian identity that did not have to pledge its allegiance to countries abroad.

This Indian-Christian identity became evident when he chose to participate in Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement which demanded boycotting institutions that received government aid, even though St. Stephen’s was a mission college dependent on British government aid.

Rudra’s explanation to his college authorities was that the strike was not anti-foreign or anti-Christian and so they were obliged to participate in the movement. All this at the risk of losing funding and favour – yet Rudra had the moral courage to do the right thing.

Inspiring Unity in Diversity

He transferred this enthusiasm to his students by encouraging them to, rise above each other’s differences irrespective of caste, religion and class. He also made it clear that a college’s strength was dependent on all students getting along with each other.

Commenting on how the college handled conflicts that resulted from this diversity he wrote, “The philosophy of sacrifice and mutual service for the unity and strength of the whole is being clearly understood. This has been a joy to the staff.” (2002, p.353).

A True Statesman

Rudra’s influence was such that the entire college embodied his kind and caring personality. He exemplified a person who had carefully processed the complexity of holding onto courage and conviction as he walked a tightrope between balancing his commitment to his country, without sacrificing his identity as a Christian.

His passion to serve and inspire fellow citizens towards unity despite diversity – is an example of a true statesman.

Sources:

Susan Visvanathan, “S. K. Rudra, C. F. Andrews and M. K. Gandhi: Friendship, Dialogue and Interiority in the Question of Indian Nationalism,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 37, No. 34 (Aug. 2002), pp. 3532-3541.

Charles F. Andrews, Mahatma Gandhi: His Life and Ideas, Bangalore: JAICO Publishing House, 2015.

Muhammad Mutahhar Amin, “The league of quiet, extraordinary gentlemen,” The Hindu, January 11, 2013, https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/society/the-league-of-quiet-extraordinary-gentlemen/article4298538.ece.